Getting trustees with LEx on board

Support across the board for bringing in people with lived experience of the charity's cause is crucial to enable success.

Barriers: Getting trustees with lived experience on board

We identified three key, interlinked barriers to getting trustees with lived experience of the cause onto nonprofit boards in the first place. Each of these three barriers is looked at in more detail below, through insights from our Lived Experience seminar participants, in their own words.

Seminar insights: three barriers

Lack of preparedness and strategic thought

- Need to work with the board before bringing in people with lived experience because there are very mixed levels of understanding of why this is important and support for it across the board is crucial to enable success.

- ‘Involvement’ is a very under resourced area in many organisations.

- The board needs to think differently, which may be completely outside their experience and they may not have the language to even have or start the conversation – this presents a development need for a board.

- Organisation fear of failing if we bring service users on board with staff. It can undermine lived experience when people make assumptions about what is the right stage of life for somebody with lived experience to join a board.

- Timing - it may not be appropriate at the initial charity start-up phase when board needs are more about legal governance experience and skills.

- Conversely, it may be key to why the charity was set up, and therefore having trustees (and staff) with lived experience adds value to the charity’s authenticity.

- The biggest barrier is that you don’t realise you need it (and nothing will fall off if you don’t have it…).

- The Chair is central to the board’s ability to welcome and support trustees with lived experience – without, it’s harder for everybody.

Recruitment practices

- Lack of clarity about what the Board is looking for by way of experience and how the Board will look to use the lived experience.

- Using the phrase ‘lived experience’ and assuming everyone knows what we mean – it’s too niche (we are excluding before we start).

- The application process: the language used puts people off. How the opportunity is promoted: go for people who are easier to reach; where the advertisement (if there is one) is placed and who might see it.

- Recruitment practices are not open and transparent and people may need support to apply, prepare for the interview, understand the expectations and legal responsibilities of the role.

- There is no central pool of support to recruit people with lived experience that could provide basic knowledge and understanding of governance and trusteeship and then match people with charities to support recruitment processes.

- Governance is often seen as ‘dry, boring, bureaucratic’ and as such it’s not something that people think of or want to be part of – if it was thought of differently, there may be more people wanting to be a trustee.

- There may be a case for combining lived experience with more mainstream trustee skills. This needs to be well thought out and articulated clearly by the board.

- Warming people up to become future trustees takes a lot of time and effort and resources to build relationships with people that people don’t always have the conscious thought to make available – it’s easier to do it differently and go to those people who already know they want to be a trustee, or have served previously.

People’s perceptions of trusteeship

- People think trusteeship is only for ‘the great and the good’ and so are reluctant.

- There is confusion about roles and responsibilities – and the level of responsibility can be scary to people who are new to it.

- Charity Commission documentation is not always conscious or explicit about what diversity means (when advising about the setting up of new charities).

- As organisations develop, they often say they want to ‘professionalise’ which means moving away from the early board which passionately set up the charity – often with lived experience - to recruiting trustees with ‘legal, property, marketing’ ie. ‘professional’ skills.

- The regular term of three years can be off putting to people.

- There is also something around stigma and prejudice: not thinking people with lived experience will be up to the job; making assumptions about the support they will need; thinking they will need too much support and not being willing to make the adjustments to board timings, for example; not fundamentally applying EDI principles to the board; getting over the bias of recruiting in one’s own image.

CCE perspectives

‘Lowering the bar’

The Parker Review: Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership (2020) which focused on racial diversity on corporate boards, makes a point that is relevant to recruiting lived experience of the cause on charity boards ie. that meritocracy is not the opposite of diversity; that both priorities should go hand in hand. As the review states: “Discouragingly, we observed that many instances of reporting …. on Board diversity policies associated their commitment to diversity (including ethnic diversity) with a reassurance that this would be implemented without compromising on merit. We suggest that this common conflation of diversity with reassurance of merit is an indicator of subtle bias that associates diversifying Boards with lowering the bar’”.

Unconscious bias and conscious inclusion

As diversity thinking starts to question the success of unconscious bias training, HR professionals and those in the leadership development space are moving towards a more proactive “conscious inclusion” approach ie. making deliberate and conscious steps to include others and ensuring that all the players in the organisation (staff, trustees, service users etc) feel psychologically safe enough to speak out and allow diversity to flourish. Put another way, to call out unconscious bias when they see it! Getting on Board offer inclusion training to help boards think strategically about both diversity and inclusion, as well as adapt their practice to ensure they make the most of different perspectives and experiences.

McKinsey offers a model for measuring inclusion - geared towards the whole organisation - but there are insights for governance and illustrates that strong diversity, equity and inclusion policies are necessary but not sufficient to foster inclusion; that meaningful actions from leaders and peers are all required along with overall organisational systems.

Check your biases at the door

The National Lottery Community Fund had a focus on lived experience leadership as part of their Leaders with Lived Experience Pilot programme in 2019. They have a collection of blogs written by lived experience leaders, and this one by Winston Allamby from Fulfilling Lives challenges us to ‘check our biases at the door and move beyond lived experience’. He asserts that "the term is so sweeping that the individual and their qualities can be overshadowed. It may be assumed that you are unqualified, limited in what you can achieve, or unable to be trusted to sit round the table. However, people are much more than just a period of their lives".

Case studies

Avoid the tick box - Ray Jenkins, Chief Executive, Emerging Futures

Ray Jenkins, Chief Executive of Emerging Futures, reflects on the complexities of including board members with lived experience.

Including trustees with lived experience of the cause can allow the organisation to say ‘we’ve done that’ (and the box is ticked).

So much is dependent on the individual. Someone willing, able and articulate isn’t always representative of our service user community. They can dominate with a particular axe to grind, and unbalance the debate, not understanding risk management, process, safeguarding, and so on.

If you’ve been ‘brought back from the brink’, you can be evangelical about a particular model of recovery, and the ‘professional’ world doesn’t always want to hear those raw experiences, so you have to pitch it right.

For a trustee with lived experience, imposter syndrome can be significant and hard to overcome. Labels such as ‘service user trustee’ can reinforce the difference, and having minutes or reports written in a different type of language, albeit with the positive intent of supporting inclusion, can come across as ‘dumbing down’ for the sake of it, and bolster the trustee’s feeling that perhaps they don’t belong there.

How to resolve this?

- Values based recruitment can help level the field in the boardroom, and this is better still when demonstrated in staff and other stakeholder interactions. People are more likely to listen and capture the ‘genuine voice’ if the organisation is values led and holds itself to account on that.

- Invest in trustee training to help all members better understand the environment and strengthen links to the front line

- Encourage open conversations and expect active listening the Boardroom.

- Keep learning!

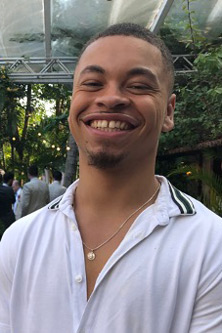

Darren Murinas, Chief Executive, Expert Citizens shares his experiences and reflections with CCE

“I had something different to offer – a life experience completely unlike that of a typical trustee”.

I didn’t come onto the board via the traditional route (headhunters or advertisement), or have prior experience of being a trustee. My entry came about as a result of a relationship built between Expert Citizens (an independent group of people all of whom have experienced multiple needs and who use their experiences to improve systems and services) and Lankelly Chase.

They recognised I had something different to offer – a life experience completely unlike that of a typical trustee – and that I could bring that lens into the boardroom. I was the first trustee on the board with lived experience of severe and multiple disadvantage, including experience of the criminal justice system.

It was daunting walking into that boardroom for the first time. I felt some fear too, not just about being a trustee with lived experience but about the whole process. I’m comfortable with the role now, but it took 6 to 12 months to feel at ease and find my voice and place.

Some boards produce huge agenda packs and expect everyone to turn up having understood the papers, rather than thinking about how they can make it easier (and more welcoming) for trustees to grasp the key points. I received considerable support from Lankelly Chase which made a real difference – running through the papers with me, answering my questions, organising software to help with my vision difficulties and helping me prepare for the meeting.

At my first board meeting, I made connections with two other trustees including a younger one who, like me, wasn’t dressed as formally as the others, and this provided a bridge. I was clear that I wanted to get to know the whole team at Lankelly Chase and see every project they were funding so, for the first few years, I was constantly out and about aiming to understand where and how the funding is spent. Some trustees discouraged this (‘you could get influenced if you get too close’) but was a great benefit to me in getting to know the organisation and the impact of our funding decisions.

We’re on an incredible journey at Lankelly Chase – rethinking the traditional and current governance model that’s 200 years old – co-creating new approaches that better reflect today’s needs. It’s exciting times to be on the board!

- See also Darren's NPC article ‘Putting People with Lived Experience in the Lead’

Mindset challenges – over reliance on networks, ‘technical skills’ and seniority’ - Eli Manderson Evans, Senior Social Justice Consultant, Ten Years’ Time.

As I started working closely with boards, I started to see that the majority of board members appeared to have been recruited through the networks of existing trustees and senior leadership teams of an organisation. These networks largely mirrored the standing experiences of those incumbent on boards, as such preventing many from outside of the ‘usual board suspects’ from even knowing about the board vacancy.

As I started working closely with boards, I started to see that the majority of board members appeared to have been recruited through the networks of existing trustees and senior leadership teams of an organisation. These networks largely mirrored the standing experiences of those incumbent on boards, as such preventing many from outside of the ‘usual board suspects’ from even knowing about the board vacancy.

Through recruiting via these networks, boards essentially preserved their distance from expertise derived through lived experience and lives closer in proximity to the social issues they served, and stood against reaching out to people with direct frontline experience and different mindsets.

This lack of inclusivity also lent itself to preserving the notions that boards must be staffed by those who are senior in their careers, from professionalised backgrounds and equipped with specific ‘hard’ skills needed at board level. The point about skills needed is one area where I often work to challenge mindsets, offering that perhaps one of the most important ingredients in the creation of good boards is passion.

You want boards to be filled with people who are deeply passionate about an issue, and not just seeking a board position to further their own career. Part of the reason why the Trustee Coaching Programme I developed is so needed is that it supports trustees with strong passion around a social issue, and with deep understanding of the area, to further develop the skills that may be needed at board level.

I think it is important that we do not position certain career milestones, higher education qualifications and more, as prerequisites to the skills needed on boards. People are capable of learning and boards are able to support learning.

Having a career in a sector which is deemed an asset to a board, being senior in your career, and having skills in a discipline such as law and finance, do not necessarily mean you will make a good trustee. In fact, often, many that have careers in such sectors may be extremely disconnected or exist very far from the issues they are discussing and making impactful decisions on at board level.

The 2027 coalition, within which my work with boards sits, sees things slightly differently and seeks to centre community expertise in grant-giving organisations. The coalition very much views the present issues of boards, in terms of their diversity deficit in relation to race, class, disability, regional spread and much more, as a phenomenon characterised by missed expertise.

By not focussing on the unique insight offered by such communities missing on boards - what they have to offer, and what including different voices in those echo chambers does in terms of building better decision-making processes - boards essentially fail to see the value of difference around decision-making tables and the subsequent opportunity to build better, more mission-aligned boards.

Useful links

Including board members with lived experience of the charity's cause – what works and what doesn’t

The Young Trustees Movement have a range of training, resources and blogs that bring insights into what works, but also in the case of this blog on Charity Board Diversity: when it doesn’t work. All of the lessons in these examples apply as much when an organisation is thinking about lived experience as it does when thinking about broadening diversity.

Lived experience on UK based INGO boards

For more information about the specific and complex challenges that arise in including those with lived experience on INGO (International Non-Government Organisation) boards, please see our website.

Centring Lived Experience

NPC has published a comprehensive and helpful guide (NPC Centring Lived Experience - a strategic approach for leaders, December 2023) about how to centre lived experience in a strategic way across the organisation, including at board level.

The guide identifies four steps:

- Prepare and explore

- Define your purpose

- Develop your approach

- Deliver

Under each section, there's information about how you might apply each step in centring lived experience on your board, which includes helpful prompts, guidance and signposting.