Building the road as we walk: leadership through uncertain times

“Charities may be in the grip of uncertainty, but many leaders have the agency, energy and will to find a practical way through”

About this resource

This online resource, exploring leading through uncertainty, is an invitation to charity leaders to celebrate the practices that support them in their leadership, as well as an encouragement to experiment with ideas, frameworks and practices that may be less familiar.

It does this by:

- capturing some of the ways that leaders in the sector lead during uncertainty;

- exploring new thinking about leading in uncertainty; and

- offering insights and practical suggestions.

The experience and wisdom of charity leaders is what forms the basis of this resource. It summarises the major themes gathered from interviews and focus groups held during 2022 with over 60 leaders, as a part of a CCE leadership research project led by Tammy Tawadros and Lisa Barry, and supported by the Bayes Knowledge Exchange and Impact Fund (KEIF). Find out more about how the research was conducted here. The participants came from a wide variety of organisations, and represented a diverse demographic in terms of age, gender, and race. We are grateful to all those leaders who generously gave their time, and openly shared with us what they had learnt from their own experience.

The resource builds on the insights we gathered, extending the findings with evidence from leadership, psychology, and social science literature and research. It addresses the answers to some of the following key questions:

- What is the lived experience of leaders in our sector grappling with the daily realities, challenges and opportunities involved in leading through uncertainty?

- What psychological and other resources do individual leaders draw on to support them during uncertainty?

- How can charity leaders lead and implement their strategic work in challenging and uncertain times?

- What do they do to help their organisation's stakeholders to thrive in uncertainty?

How to use this resource

Building the road as we walk is divided into three main sections, each of which deals with one of the dimensions explored in the research:

Within each section you will find subsections about:

- What you told us: Insights from our surveys and conversations with charity leaders

- What works: Perspectives and practical tips on what works in practice

- What the science says: Explorations that go a little deeper and offer evidence-based ideas and tools for leaders to use, together with useful links to related materials.

1. The person of the leader

What helps you on an individual level to lead in uncertainty?

Well-being and resilience

While many charity leaders we talked to have well-established exercise and relaxation routines, some struggle to maintain balance or take much time for themselves, whether for self-care or to reflect on their work.

What you told us

“We are well aware that eating healthily, getting enough rest, sleep, and exercise, and having a social life is important."

“For me it is more about getting beyond the basics and making sure my resilience isn’t worn away by the constant battle to keep [the organisation] going.”

“My two biggest takeaways have been remembering to stop to take a breath and getting into the habit of having thinking and reflecting time and booking it in the diary.”

What helps?

“Taking a lunchbreak: dancing in the street!”

“Climbing. It helps me master my emotions.”

“Accepting my limits.”

“Having support and a network.”

What works

- Live in the moment, be present.

- Don’t lose focus on your own wellbeing.

- Find out what works for you to stay sane and healthy, and make it your intentional practice.

- Switch off purposefully to keep a sense of proportion.

- Don’t be myopic – remember there is life outside the office.

- Focus on process not outcome.

- Learn to accept that our reactions come in waves of self-doubt - often followed by resilience.

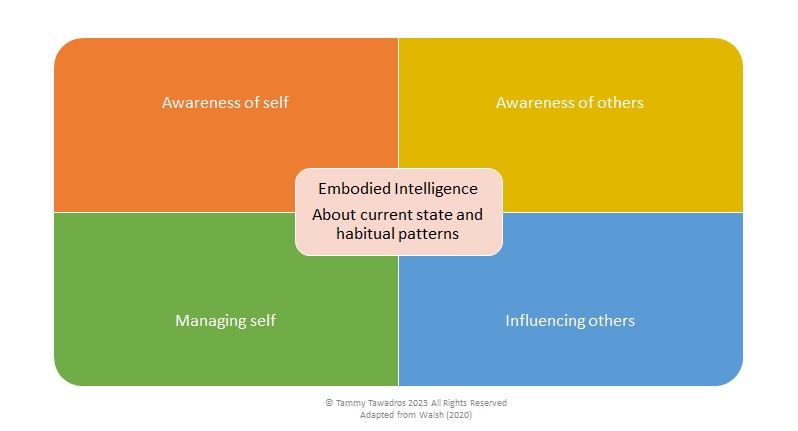

What the science says - Embodied Intelligence

Embodied Intelligence

The evidence from neuroscience and elsewhere points to the importance of what Mark Walsh (2020) calls 'embodied intelligence'. See below for a model of embodied intelligence.

Ways to access embodied intelligence

Walsh (2021) suggests nine different ways to access and enhance embodied intelligence. See below for an overview of these nine portals.

9 Portals to Embodied Intelligence

- Open & upright posture

- Relaxation: letting go of tension

- Breathing: taking a deep breath or two

- Intention: aim & focus

- Movement: do something physical

- Here & now awareness

- Acceptance: of what you can’t control or influence for the time being

- Responsiveness: adapting & flexing

- Imagery: imagining & picturing shifts our state & our perspective.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

What the science says - Building self-awareness

Leading in uncertainty is inherently anxiety provoking, and it is likely to present us with demands and stressful situations that trigger our nervous system to respond to these as ‘threats’. We know that as humans we are built, and biologically primed, to react to danger and to threats, so that we can survive and find safety. Our nervous system responds ‘automatically’ to fear triggers. It doesn’t matter whether that trigger is a tiger coming towards us, an unpleasant email that lands in our inbox, the prospect of a cut in funding to the organisation, or something that reminds us of a past trauma - our nervous system doesn’t differentiate. Uncertainty in the external environment can also act as a fear trigger. Fear activates our nervous system’s threat response of fight, flight, or freeze.

Leading in uncertainty winds you up. We might experience fight-flight states as a sense of feeling ‘wound up’, ‘ready to spring’, like a jack-in-the-box. Alternatively, we may experience a felt sense of being vigilant, on ‘high alert’, and perhaps unable to ‘switch off’.

Overload plus uncertainty can shut you down. Freeze states can often accompany times when we feel overwhelmed by demands, and ‘last straw’ moments. Those moments when yet another task or problem comes your way when you’re already super busy, or one more thing goes wrong at the end of a long or a difficult day. We might feel paralysed with disbelief, numb, unable to register – ‘shutting down’. Uncertainty itself can lead to a freeze-like state, or it might compound the experience of overwhelm and shut down.

Know what state you are in! Being able to recognise what ‘state’ you are in at any given moment is important because our nervous system reactions are very fast. What’s more, the reactions happen outside our awareness, before we have registered a reaction, and before our brains have formulated a thought or interpreted an event.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

What the science says - Befriending your nervous system

"Our nervous system is always trying to figure out a way for us to survive, to be safe."

Dr Stephen Porges, 2022

Give yourself a moment of pause

This can be in the form of a deep breath, a movement, a stretch, or closing your eyes or giving them a rest by looking to the middle distance, looking, and smiling at a colleague. Whatever works for you to introduce a pause or slow the pace of your system can be very grounding, counteracting the ‘high alert’ state that has been activated outside conscious awareness.

Research backs up what many spiritual and other practitioners have known for millennia - that slowing down breathing and meditative breathing can send the message to our nervous system that we are safe. This enables us to think more clearly and creatively.

See for example:

- Breathing Happiness, TED Talk by Emma Seppälä PhD. Science Journalist and author, and the Associate Director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University.

- Nestor, J. (2021) Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. Penguin Books

Give yourself a positive anchor

This can be in the form of a pleasant memory of a person, place, or moment. Or it can be a simple activity that brings you joy, pleasure or satisfaction.

Create a library of positive anchors

Moments, micro-moments, short, pleasant activities and/or the memory of such moments and activities can provide you with a reliable support in your day. Making it a habit to use or recall your anchors can become a simple and practical way to resource yourself when the ‘going gets tough’, to bring yourself back into a state of equilibrium and a sense of safety.

Deb Dana, a leading specialist in this field, recommends identifying positive anchoring experiences and keeping a list of these that you can return to and use.

Building a library of positive anchors

Use the categories and prompts below to build your library.

- Who. Think about the people in your life. Make a list of those who make you feel safe and welcome. You may have a pet who brings you that experience. Think of people in both your personal and your professional world.

- What. Reflect on what you do that brings you moments of joy, simple pleasure, small actions that feel nourishing and connecting.

- Where. Walk around your local area, your workplace (or beyond). Or visualise physical places that you have visited. What are the places that feel special, that cue you to feel safe, to feel ‘warm inside’, or that you have a special connection with.

- When. Identify times when you have felt safe, calm, and connected. Bring them to mind and conjure the sensations you had. Write these down in as much detail as possible.

- Build your library. Decide how you want to put this together. This might be in the form of a notebook or journal, in which you include any relevant images or photos. Or you may choose to put up post its. Make sure that you can access your library easily.

Adapted from Dana (2020)

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

What the science says - Befriending your body

"We’ve taught the body – our nervous system – to be numb, not to be aware of our bodily needs, to sit still. We tend to shame people who listen to their body."

Dr Stephen Porges, 2022

There is often a disconnect between the way our body feels, our physical sensations, our physiological states, and how we come to interpret these. Stress manifests in our body well before we register it consciously, and usually before we can make a choice about what we feel, think, and do. Becoming aware of our fleeting embodied responses can be key.

Recognising our habitual embodied reactions helps us to cultivate and learn how to respond more skilfully and resourcefully in stressful circumstances and in a radically uncertain context. The evidence from biology and neuroscience is overwhelming. Without listening to our bodies, without being aware of our embodied reactions, we are not able to shift beyond the grip of flight, fight or freeze. All we can do is put a brave face on what our physical being is manifesting - a layer of laminating behaviour that sits on top of our stress or survival reaction.

Directing our attention to our posture is one way that we can befriend our embodied self. Our natural reaction to fear and stress is to hunch and close up. Changing our posture to become more uplifted, by standing or sitting upright with both feet on the ground for example, physically changes how we think and how we talk about our feelings and thoughts. Spending more time in a centred posture can help us change our perspective and see more options and possibilities. This in turn, can help us meet the challenge of uncertainty with greater equanimity and focus.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

What the science says - Befriending your mind

Using self-talk to befriend your mind

There is mounting research evidence which shows that self-talk can be hugely influential on performance and confidence across many different endeavours, from sports to leadership. Using self-talk as a deliberate strategy is based on the premise that what people say to themselves ‘internally’ and therefore what they think, influences how they feel and how they behave.

Our inner monologue can often be quite a negative one, with an inner voice that may be critical and unhelpful. When the external context is unpredictable and/or rife with economic, political, and social disruption, befriending our minds through our self-talk can become particularly important. It can counter the harsher or more critical internal voices leaders may encounter, and it can also help us to increase self-confidence and a sense of agency. Evidence also suggests that self-talk plays a part in helping us regulate our emotions, cope with difficult experiences, and facilitate perspective-taking. Moreover, using self-talk as a strategy seems to work better in novel situations, than when carrying out familiar tasks. This suggests that self-talk may lend itself even better to situations where leaders are facing self-doubt, external uncertainty, or when they are making decisions during uncertainty.

See also: Being uncertain might make you a better leader, Tammy Tawadros

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Using reflection to befriend your mind

“Booking myself time to think in the diary can feel like an indulgence. In fact, it’s what we are paid to do.”

“Reflecting alone on a walk, and with others who are in the same boat has been a lifeline.”

“What we need is help with ways to commit time and energy to developing our leadership skills and thinking - creating moments for ourselves.”

Peer relationships

Many senior charity leaders frequently feel lonely and alone. They draw comfort from the knowledge that other leaders in the sector face similar challenges and that they share many of the same experiences, especially feelings of self-doubt and ‘imposterdom’.

While they value peer connection and support, many are surprised at just how important this can be at times of crisis and uncertainty, and how crucial a network of peer relationships can be for personal and professional well-being and resilience.

“Every senior leader needs a 'professional posse'!"

Christine Fogg, Honorary Visiting Fellow at Bayes Business School

What you told us

The reflections below capture some experiences of the value of talking and sharing with peers:

“Having other people outside the organisation who understand makes all the difference.”

“My relationship with my colleague, who works across the country and in a very different part of the charity world, has been absolutely invaluable - it is like a sacred space - the only place I can be myself and speak my truth. I think it is the same for her. “

“I felt much less emotionally exhausted, and though it is a bit odd to say this, I realised that I had accomplished a lot more in my role than I realised.”

“Somehow, I never believed that sharing different experiences and also being in the same boat would be so important. It is such a support and a relief!”

“The organisation faced the same trials and tribulations, not to mention turbulence and though I have rarely felt more challenged - being part of a network, being part of something bigger seemed to ease the stress.”

What works

- Think of it as an investment! You will always have someone whose brain you can pick. Call an executive friend!

- If you’re not comfortable asking for help or you don’t have a network, at least you can be there for someone else.

- Talk to others at every chance you get. Don’t go it alone.

- It helps to be reminded that you are not alone, and that there are others facing the same self-doubt and struggles that you face.

- Being exposed to diverse thinking, and a diverse group or network, brings a wealth of new and different information, knowledge, and perspectives.

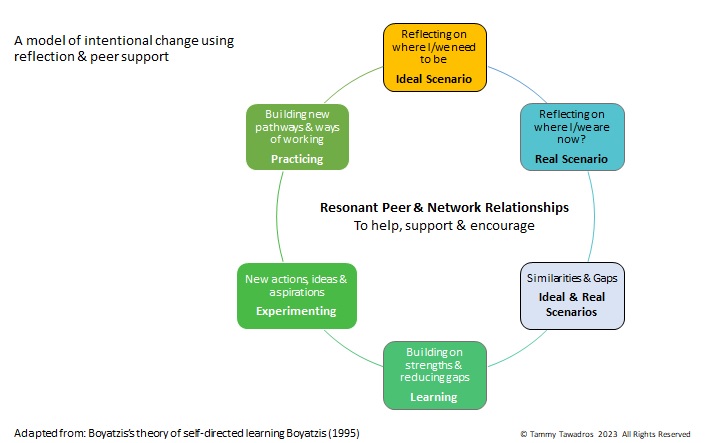

What the science says

Below is a model of intentional change that shows how combining individual reflection with peer support would enable leaders to capitalise on inherent and available resources during uncertainty, to generate new ideas and options.

Resonant Peer & Network Relationships: To help, support and encourage.

- Reflecting on where I/we need to be, ideal scenario

- Reflecting on where I/we are now, real scenario

- Similarities and gaps, ideal and real scenarios

- Building on strength & reducing gaps, learning

- New actions, ideas and aspirations, experimenting

- Building new pathways and ways of working, practicing.

The power and importance of connecting with others.

Feeling lonely, whether ‘at the top’ or elsewhere, and not having people to share your problems and dilemmas with is the single most injurious experience for health and well-being. In terms of predicting poor health and well-being outcomes, loneliness is worse than lifelong smoking!

As humans we cannot thrive without a sense of connection with others, without relationships in which we can ‘tune in’ to one another’s needs and share experiences, including the issues and problems we face.

See for example:

- The Power and Science of Social Connection, TED Talk by Emma Seppälä PhD.

- Pinker, S. (2015) The Village Effect: Why face-to-face contact matters. Atlantic Books

Resilience is a social sport!

Although we tend to relegate resilience to the realms of the individual, being with others, particularly during times of uncertainty is something that positively feeds our resilience as leaders. Whilst leaders in our sector are often concerned with the resilience of the team and the organisation, they are often surprised to find that their own personal and leadership resilience is in part drawn from groups of peers and other networks.

Although few studies pay specific attention to the part that peer groups and networks play in boosting leaders’ resilience, there is a good deal of evidence that social support and social connections militate against the impacts of adversity and stress, including disruptive change and prolonged uncertainty. We have a good deal of evidence to show that for clinicians, health practitioners, and leaders for example, being part of a peer group seems to have a positive impact on psychological well-being and mental health. Research also tells us that those leaders who deal with adversity and uncertainty best, are those who have close and confiding relationships during difficult times. Many consistently emphasise the significance of relationships in their ability to be resilient.

See for example:

- The Hive Effect: Building resilience in groups, Tammy Tawadros

- Earned Resilience and Learned Optimism, Tammy Tawadros

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

2. Leading the organisation

What helps you as a leader respond to dilemmas and tackle strategic choices that your organisation faces during disruption, change and uncertainty?

Learning from experience

Leading through the pandemic proved to be exhausting, but also exhilarating. For many leaders, it inspired greater self-confidence and provided the opportunity to experiment and learn.

“The pandemic showed organisations they could survive in ambiguity, and this gave us confidence”

“This was an opportunity for leadership to get things done quickly, to be brave”.

“We had freedom to try new things. All the rules had changed.”

“Navigating uncertainty was a huge team building opportunity!”

Looking back on past experiences of leading through uncertainty, leaders tended to point to four important approaches/stances that help:

- Debunking heroic leadership

- Being flexible

- Collaborating intensively

- And holding on

Debunking heroic leadership: resisting myths and unrealistic expectations about individualistic leadership

What you told us

“It’s better to lead through others than to try to be a heroic leader!”

“My job is not to know everything, but to know enough. And to know who I can go to for expertise.”

“You’ve got to share responsibilities, or you’ll go mad.”

What works

- Keep noting your own achievements – don’t be hamstrung by that human desire to compare yourself to everyone else.

- Don’t discount your achievements as a leader, or underestimate how much you accomplish through others.

- Don’t forget to keep pushing decisions out from the centre.

What the science says

The myth of heroic leadership

Although the myth of heroic or Great Man leadership wasn’t often explicitly mentioned, it was often implied during the conversations we had. These myths have influenced leadership theories and leadership development. They have also unwittingly and unconsciously shaped our expectations and our thinking about leaders, and about our leadership.

Many would argue that heroism and Great Man leadership are both irrelevant and unhelpful, if not sexist and potentially toxic. Some maintain that we consistently look for and recruit for the ‘wrong’ leadership qualities. Although there have been numerous critics of these ideas over the years, they do seem to persist across society and in the charity sector. Perhaps this is partly because whether as individuals or collectively, we tend to want to place our faith in an ideal, transcendental leader, who can achieve the impossible! It is an ideal that will clearly always find leaders wanting.

The tyranny of should

It was Karen Horney (1950), an often-overlooked psychoanalyst, who was one of the first to explore this phenomenon. She identified the psychological tyranny we subject ourselves to when our self-talk and core belief is that: ‘I should know all the answers’.

One of the themes that recurs consistently for leaders, especially as volatility and uncertainty increasingly pervade the external context, is that of not knowing enough or not being good enough. They often feel that they should have the answers, and therefore, they must be imposters or interlopers who don’t know what to do in the face of unending change, disruption, and uncertainty.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Being flexible: letting go of red tape, adapting activities and processes

What you told us

“This was a chance to throw bureaucracy out the window.”

“The ‘people people’ did the best through it all; rules and regulations just didn’t cut it.”

“Taking different roads to achievement, and being clear as an SLT that we’re okay with that …”

“Not being afraid to change and adapt what we did to meet the circumstances. We realised we could manage risk quickly, for example.”

“Not worrying about doing everything to plan – but still having a plan.”

“The pandemic showed organisations they could survive in ambiguity, and this gave us confidence.”

“I find complexity fascinating. Chaos perhaps not so much…”

What works

- Never let excellence be the enemy of ‘good enough’.

- Don’t be too wedded to policies and procedures as long as you’re ‘safe and legal’.

- Know when to survive and when to thrive - give yourself permission not to grow if you’re in the grip of chaos or crisis.

- Find opportunities in crisis and uncertainty to do things differently.

- Seize the chance to be entrepreneurial - there are ‘small’ ways to add value by going digital, or through income generation.

What the science says

Being flexible: shaping not planning

"During great uncertainty, though nothing can be planned, everything can be shaped."

Anon.

Research suggests, as the leaders we spoke to also said, that being flexible about what the organisation does and how it does it, is key during periods of crisis, disruption and uncertainty. Building on this, we include some of the current thinking and evidence about leadership, and consequently organisational practices that enable and support flexibility. These are practices (i.e. repertoires of skills and behaviours) that are eminently doable and learnable. They include the capacity to embrace complexity, to sit with ‘not knowing’, and to nurture flexible thinking.

Embracing Complexity

Embracing complexity encompasses the capacity to adapt decisions and manage contradictions and tensions. What we do as leaders in the charity sector, is in any case, often laden with paradoxes and tensions. Uncertainty in the external context adds greater challenge to strategic planning and decision-making.

Being adaptive is about flexibility and innovative problem-solving, finding new solutions to new and unique problems that arise in the current context. However, it is also about being able to sit with not knowing, until new possibilities start to emerge and new learning can happen.

Allowing not knowing, nurturing flexible thinking

“Even when we can hold onto both, in managing the tension between two equally balanced options, we are faced with a different question. How on earth do we build strategy without knowing very much about what the future holds, what the future will bring?”

“I’m getting better at knowing that I don’t know. It helps.”

The state of not knowing can feel like the antithesis of what leading should be. Yet to get through the experience successfully, leaders are often ‘forced’ to consider what resources or knowledge they have. Sometimes they recognise a skill they have, or acquire greater skills, for example managing their emotions or those of others during uncertainty. Or they may enhance their knowledge or gain a new perspective on the external world. Whatever skills or knowledge the leader develops or builds, may be applicable to future problems. It may simply be the capacity to sit with not knowing, to slow things down, and thereby allowing time for reflection. When leaders develop new capacities, new skills, and new ways of seeing and understanding, they can become more able to deal with an unpredictable world. When leaders develop new pathways to get from here to there, they are more flexible in confronting the uncertain and unknown. These flexibilities build on each other.

Flexible thinking

Our tendency as humans, when we are in the grip of uncertainty, is to look for certainties, to pursue clear lines of cause and effect, to go after the answer or the action we need to take. The bias in conventional thinking and leadership is towards known cause and effect relationships, tried and tested methods, and ‘best practice’. All of these may work better in a world that is more predictable and stable. A bias in favour of predictability militates against the flexible thinking and agile responsiveness that is needed to respond during periods of volatility and uncertainty.

See below for a model to help you adapt to a more flexible approach and greater responsiveness as you lead through uncertainty.

Complexity thinking

| The Bias | The Flexible Adaptation |

|---|---|

Cause and effect is linear, I can simplify the story | Rehearse many different ‘what if’ scenarios |

There is a good fit solution, ‘best practice’” | Get multi-source perspectives and data |

Agreement and consensus will help | Factor in different and dissenting views |

As a leader I need to take control | Use delegated decision structure |

Going it alone to solve the problem | calling on collective experience and wisdom |

Act self-sufficiently. | Going wider to collaborate |

See also:

- The Problem with Best Practice, Shane Snow Fast Company (2015)

- The Surprising Habits of Original Thinkers, TED Talk by Adam Grant, Organisational Psychologist, and Professor at Wharton School of Business in the U.S.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Collaborating intensively

What you told us

“It really helped to have a space to grapple with big decisions together. Not just rubber stamping.”

“Having a supportive board who are engaged and accessible, allowing collective responsibility for decisions and sharing accountability if things go wrong, makes all the difference.”

“It was relying on a senior team who can really critique decisions - not being precious about that if we have built trust and respect.”

“I really learnt the value of continuous feedback, not being afraid of honesty. Being a sounding board for each other in the organisation."

What works

- Exercising discipline and communicating your intention to your team.

- Being honest, open, and joined up – there’s no need to ‘air dirty laundry’ elsewhere.

- Seeing trustees and the chair as being part of the solution - not leaving them waiting for an invitation.

- Capitalising and building on formal and informal networks, including outside of the sector, to build and influence change.

- Remember the power of creative agency!

What the science says

The literature is unequivocal that successful collaboration at times of crisis, duress, and uncertainty requires initiative, imagination and interpersonal skill. Our impression is that these are qualities which charity leaders demonstrate in droves. The evidence also points to the fact that influence and success appear to hinge on the degree of personal connection and familiarity between key actors, and not on what may be organisationally ‘decreed’ or expected. In other words, successful collaborations, which meet the desired outcomes, usually flow from the networks of relationships that help leaders and other stakeholders deal with situations that don’t fit neatly into established processes and structures.

The research clearly supports what many charity leaders already know, and what they shared with us, that leaders who harness and balance formal and informal networks and relationships are able to respond more readily and effectively to disruptive change, volatility and uncertainty.

Below we offer two resources:

- A checklist of questions which can serve as a ‘rough and ready’ analysis and health check of your organisational social network.

- Three practical scenarios which leaders shared with us which highlight the benefits of taking a flexible approach and using more relational and collaborative endeavours.

Social Network Health Check

- Do you have a clear picture that ‘maps’ the wider charity and community network within which you operate?

If not, you can simply draw a sociogram picture which depicts individuals and organisations you are connected to as a leader and/or an organisation. You can represent individuals as smaller ‘dots’, relative to organisations and use different colours to distinguish them. You can also represent the strength or quality of connection by representing the connecting lines between ‘dots’ in varying colours, thickness or shape.

See links below:

- Look at the sociogram you have created. What do you notice about the pattern of relationships that ‘hold’ you in a group with others?

- Which individuals or organisations look like the most central ones? Which may exert the greatest impact on you/the organisation about access to information for example? What about decision-making? What about other domains of activity? This information can help you get a clearer perspective on relationships and interdependencies and help inform actions and decisions.

- Where are the critical junctures in the diagram?

- Which individuals or organisations look like the most peripheral ones? Do you need to engage them more? What expertise, information, perspectives might they hold?

Scenario 1: Using dialogue and debate when resources are tight

One charity leader told us how she insisted on holding the space for a series of cross organisation retreats, and rather than a two-day whole organisation residential which they could not afford. She decided to have several short conversations with a different mixed, cross-section of stakeholders to talk about how they experienced the pandemic, and what their hopes for the future were. This sparked so much enthusiasm that she organised a further round of similar meetings to work on planning a flexible rolling strategy.

Scenario 2: Using personal and practical processes rather than procedures

In one organisation sticking to the letter of procedure would have meant a series of long management investigations into grievances raised and setting disciplinary processes in motion. The leader in question chose what she called a 'courageous experiment' in which she paused, with everyone’s agreement and after taking HR/legal advice, the formal processes underway. Her hunch was that the lack of in-person contact, together with the uncertainty surrounding the future of the organisation, were contributing to the conflict that had arisen, and led to the formal grievance being made. In the meantime, she convened, an in-person meeting facilitated by an external and independent colleague for everyone involved to share their thoughts, feelings and perspectives about the issues which led to the grievances and disciplinary processes to be invoked. Meeting informally made it possible to understand one another’s behaviour and intentions better and helped to restore trust between colleagues.

Scenario 3: Repurposing a forum set up during the pandemic

During the pandemic, the CEO of the organisation created a forum for frequent and regular dialogue between members of the executive leadership team during the pandemic. This has now been converted into a working group which is looking at the external impact of the ‘cost of living crisis’.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Holding on

What you told us

“…Trying to act according to my values and principles - that kept me going - and knowing that I had made principled decisions.”

“Letting people know that decisions are being made, and not skirted.”

“Hanging on to strategy and to purpose was very important.”

What works

- Living our values.

- Communicating, communicating, communicating.

- Framing trade-offs very specifically.

- Naming the worst-case scenario, and prioritising against the worst case.

3. Leading stakeholders

What helps you help stakeholders to thrive in and through uncertain times?

Relationships and trust

Charity leaders have learned much from their experiences during the COVID 19 crisis. The demands of that time, in circumstances which were deeply unsettling and unfamiliar, far from derailing many leaders, their organisations and their people, offered extraordinary opportunities for experimentation and valuable learning. Demonstrating to stakeholders that they are actively engaged in responding to challenges and making decisions is important for leaders to build confidence and trust. At the same time listening, talking, and communicating honestly and often are also key.

What you told us

Listening and dialogue build understanding

The importance of investing in relationships with all stakeholders and building trust during uncertainty was highlighted as paramount by all those who participated in our research. Leaders also emphasised the need for continuous listening and dialogue to develop understanding of stakeholders’ own unique experience, their context and their particular or individual needs. For example, understanding that volunteers’ motivations may be closer to those of beneficiaries, leading them to worry more about the impact of uncertainty. Or recognising individual differences in the need for support through uncertainty in that some may find it much harder to cope with than others.

Transparency and clarity are essential

Meeting, preferably in person, and being clear on what is wanted from those meetings was seen as a foundation for reinforcing positive relationships and a collegiate culture. This posed some conundrums for leaders about ‘return’ and hybrid and virtual working. One of the overarching messages, however, was that offering up-to-date information, in a climate of transparency, where all stakeholders hear answers together, was critical to building trust.

We touch on the theme of bringing people together in the what the science says section on collaboration above. In the sections that follow below, we also make connections between the themes that emerged about leading stakeholders with the research findings on compassionate leadership.

What works

- Talking with others through the challenges and changes that happen.

- Even when feeling anxious and burdened, leaders can offer opportunities for stakeholders to express their concerns and share suggestions.

- Listening settles people and makes them feel less powerless.

What the science says

Coming together to build relationships and trust

During times of intense or rapid change, and in uncertainty, our sense of connection and shared purpose may be disrupted. The opportunities we have to come together collectively may be reduced. Moreover, our psychological capacity to make sense of our emotions and of what is happening around us may be eroded, particularly if our threat response (fight, flight, freeze) has been activated. This impairs our working memory, our problem-solving ability, and it diminishes our capacity for insight and compassion. People are ‘reduced’ to operating in survival mode, which in turn limits the potential to deal with uncertainty and complexity.

Collective activities that enable groups of people to share and make sense of their experiences and express their feelings can have far reaching positive consequences. Sharing experiences, feelings, perspectives, and stories can engender a sense of connection and shared purpose. Moreover, taking part in dialogue, in shared endeavours and in activities that include narratives and storytelling, have been shown to reduce stress and boost well-being for leaders and organisation members alike.

Valuing people, and making people feel valued

One consistent theme that came through, was about coming together to build trust, through regular touch points and check ins, to share successes, but ultimately to ensure that people feel valued in the midst of disruption and uncertainty.

Many charity leaders were conscious of the stress and suffering that many of their stakeholders experienced during the COVID 19 pandemic. Many told us how during and indeed, since the pandemic was at its height, they witnessed organisation members and stakeholders experience distress and hardship. They empathised greatly with these experiences of pain and struggle and offered practical support wherever possible. Many leaders pointed to the solidarity and trust this created within the organisation, and across different groups of stakeholders.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Compassion and compassionate leadership

Although empathy and compassion were seldom directly referred to by respondents in our research, they were occasionally implied. Given their acknowledgement in our sector and their importance in the organisational and leadership literature, we felt it was important to signpost key messages from the science.

"It takes courage and strength to be empathic, and I’m proudly an empathic compassionate leader."

Jacinda Ardern, 2018

What the science says

Leadership research shows that compassionate leadership brings many benefits to individual stakeholders and to the organisation. When leaders respond to difficult events with compassion, they foster individual and organisational well-being and resilience.

Compassion is contagious - in the sense that being at the receiving end of compassion from self and others, means we are more likely to offer compassion, thereby creating a virtuous cycle. Ultimately, compassion creates a sense of safety and connectedness in teams and organisations. This provides a strong buffer to fear and threat, which in turn encourages greater trust and collaboration.

The seven benefits of compassionate leadership are:

- Healing

- Trust

- Commitment

- Engagement

- Positive emotions

- Performance

- Belonging

Adapted from the literature © Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Three ways you can build compassionate leadership

- Practice self-compassion. Do you show yourself the same consideration and kindness that you might offer to those you lead?

- Balance your attention. Do you focus on the well-being and contribution of your people, as much as you do on other aspects and tasks of leadership?

- Create a forum to talk. Do you (or does your organisation) offer regular opportunities or a forum for people to notice the emotional impacts of their work, including feelings about change and uncertainty?

Twelve questions to ask yourself about fostering compassion in your organisation

Questions to help leaders identify some of the activities that foster compassion in their team and wider organisation:

- Do I actively promote a culture in which people trust each other?

- Do I encourage a climate of caring and non-judgement? So that people know that if they talk about their problems, other team members will not judge them, and they will listen and try to help?

- Do I actively encourage and empower others to respond to a colleague’s suffering?

- Do I show care and concern towards people in my team/organisation?

- Do I understand the value of sharing problems with others?

- Do people in my team know that I will try to help and support them if they have a problem?

- Are people in my team/organisation in regular close contact (e.g. through face to face daily or weekly meetings)?

- Is there a strong relationship between people in my team/teams elsewhere in the organisation, which makes them feel joined up as a team, connected, seen, felt, known and not alone?

- When people in my team/in teams elsewhere in the organisation, notice a change in the condition of a colleague, do they feel comfortable about inquiring further?

- Is it a norm in my team/ teams elsewhere in the organisation, to know about each other’s lives and pay attention to any distress and suffering that a colleague might be experiencing?

- Do people in my team/ teams elsewhere in the organisation, feel safe in sharing their personal problems, issues, and challenges with each other?

- Do people in my team feel they can openly express their emotional distress?

Adapted from Roffey Park (2016)

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Beating burn out

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation…”

Audre Lorde, 1988

We know that charity leaders work long hours and must deal with overflowing workloads. They find themselves absorbing the many demands of stakeholders. At the same time, they have to take care of their own needs, in an ‘always on’ and increasingly hybrid workplace.

What you told us

Many underlined the need to conserve and replenish their own personal resources for psychological and physical well-being.

“…Reminding myself that owning everyone’s problems is too much for anyone; support people as much as possible, but recognise your limits.”

They were also conscious of their responsibilities as leaders and the need to support their people’s well-being.

“When the leader gets a cold, the organisation gets a cold.”

“I think a lot about role modelling healthy behaviours, and consciously reflecting on organisational routines and rituals such as going for a drink after work: is this helping us?”

“One of the challenging things I find as a leader is balancing the tension between instilling optimism re the future but being real about the challenges ahead.”

“[One of the] questions I ask myself is how can I be less hard on myself when things don't go according to plan. As a leader I feel accountable to others and myself and sometimes it's being courageous to say you've done all you can or you now need to stop what you're doing. That's incredibly hard when things around you are up in the air and you want to deliver/achieve an outcome.”

What the science says

Burn out comes from empathy fatigue, not compassion fatigue!

We know that empathic distress, as distinct from compassion, leads to burn out. Empathic distress is not so much concern, but rather too much empathy, combined with prolonged feelings of distress, of feeling with, as opposed to feeling for others. Burn out results from the need to protect oneself from empathic distress, and which leads us to turn away/shutting down.

When someone feels compassionate, the feeling is other-focused, positive, and protects against burnout whereas empathy involves taking on the negative feelings of others, compassion invites feelings of love and warmth toward others.

The antidote therefore, is to turn empathy into compassion.

See links below:

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Hope

The topic of hope was highlighted as profoundly important by several of the leaders we interviewed. It was highlighted particularly during the forum discussion groups we held. Many believe that charity leaders play a critical role in giving hope to their stakeholders during uncertainty.

Although this proved to be a less well elaborated theme, when we returned to reading what respondents told us through the lens of the literature evidence, we identified two sets of practices referred to throughout by respondents. It seems that with regard to hope, the leaders we spoke to were doing much to give and sustain hope without making an explicit link to this, and perhaps without having articulated or crystallised how these practices benefited stakeholders. There were three sets of recurring themes which we identified in terms of:

- Listening, empathising, acting, and communicating in a genuine and transparent way.

- Helping people to come together, to share experiences and to collaborate and take action.

- Taking the opportunity to reinforce purpose, and to enact values; staying focused on the impact that the organisation is making.

All of which link back to the all-important theme of leaders offering hope.

What the science says

Overall, the research points to two key areas:

Securing a relational baseline for hope

The first is concerned with helping stakeholders to secure the greatest level of certainty and well-being now, in the present, by boosting psychological well-being and engendering trust (see for example Xu et al, 2016).

- Psychological well-being. Helping people to have more agency, autonomy and feel that they belong can give them a secure base from which to view the future and to act. In this, certainty seems to come from extending and supporting caring relationships (including with the leader), and ensuring that stakeholders look after their own well-being.

- Trust. There can be no hope without trust. As we have noted above, charity leaders underline the importance or relationships, dialogue, transparency, and communication, as well as the need to give confidence in their response to and decision-making in uncertainty. In other words, how the leader makes sense of uncertainty and makes decisions seem to be particularly important.

The future

Hope by its very nature is a belief in a better future.

Hope that the future can and will be better can energise and mobilise stakeholders even during times of extreme stress and uncertainty (see for example, Dutton & Spreitzer, 2014).

Overall, leaders can give hope by articulating a clear purpose and vision, by showing that they are optimistic and resilient, and by supporting and involving their stakeholders. (see for example, Shahid & Muchiri, 2019) This touches on an inherent contradiction - that leaders in uncertainty exercise control in some respects and empowerment in others.

© Tammy Tawadros 2023 All Rights Reserved

Conclusion and summary

Overall, the canvas of experiences and perspectives from our research are complex and nuanced. Nonetheless it may be possible to discern some overarching messages. Firstly, that it is the person of the leader, and not their personality or traits, nor their heroic leadership acts that help during crisis and uncertainty. Rather it may be more about how they manage their energy and empathy and their own uncertainties.

Connecting with peers, colleagues, boards, other organisation members, and beneficiaries all make a huge contribution too, not only to personal resilience, but also to the resilience of the organisation and its stakeholders. It is about balancing confident sense-making with adaptability, with enhancing trusting relationships through communication and clarity, and inviting stakeholders to participate, collaborate and take collective action. Many of the practices we heard about contribute to a charity leader's capacity to give hope to their stakeholders in uncertain times, particularly those which support psychological well-being in the present and a belief in a better future.

Join the conversation

We would encourage you to engage with The building the road as we walk resource on social media and share your own experience of leading through uncertainty. Please tag @BayesCCE in your post.

Useful links and resources

Associated blogs by Tammy Tawadros

- Being uncertain might make you a better leader

- Earned resilience and learned optimism

- Living and leading in uncertain times

- The Hive Effect: Building resilience in groups

Well-being and resilience

- 10+ Mindful grounding techniques, Positive Psychology

- About Wellbeing, What Works Wellbeing

- Breathing Happiness, TED Talk by Emma Seppälä PhD.

- Health and wellbeing at work, CIPD

- Leading on empty: How leaders drive their people to burnout, The Energy Project

- Neff, K. (2011) Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself.

- Nestor, J. (2021) Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. Penguin Books

- Reflectors' Toolkit, The University of Edinburgh

- Resilience: Build skills to endure hardship, Mayo Clinic

- Ridings, A. (2019) Pause for Breath: Bringing the practices of mindfulness and dialogue to leadership conversations.

Peer relationships

- How leaders create and use networks, Harvard Business Review

- Schein, E., Schein P. (2018) Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust.

- Pinker, S. (2015) The Village Effect: Why face-to-face contact matters. Atlantic Books

- The power and science of social connection, TED Talk by Emma Seppälä PhD.

Being flexible

- How to sustain your organization's culture when everyone is remote, MIT Sloan Management Review

- Psychological safety in remote and virtual teams, Psychological Safety

- The problem with best practice, Shane Snow Fast Company (2015)

- The surprising habits of original thinkers, TED Talk by Adam Grant, Organisational Psychologist, and Professor at Wharton School of Business in the U.S.

Collaborating intensively

Compassion and compassionate leadership

Beating burn out

- Five ways to combat compassion fatigue, Royal College of Nursing Magazine

Other

- It takes versatility to lead in a volatile world, Harvard Business review

Research references

Dana, D. (2020) Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection. WW Norton and Company.

Dutton, J.E., and Spreitzer, G.M. (.Eds) (2014) How to be a Positive Leader: Small actions, big impacts. Berret-Koehler.

Dutton, J.E., Workman, K.M., and Hardin, A.E. (2014) Compassion at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 277–304.

Gilbert, P. & Choden. (2013) Mindful compassion. London, UK: Constable-Robinson.

Horney, K. (1950) Neurosis and human growth. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Kanov, J., Maitlis, S., Worline, M.C., Dutton, J.E., Frost, P.J., and Lilius, J. (2004) Compassion in organizational life. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 808–827.

Ramachandran, S., Balasubramanian, S., James, W.F. et al. (2023) Whither compassionate leadership? A systematic review. Manag Rev Q (2023).

Roffey Park (2016) Are you a compassionate leader?

Shahid, S. and Muchiri, M.K. (2019) Positivity at the workplace: Conceptualising the relationships between authentic leadership, psychological capital, organisational virtuousness, thriving and job performance, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 494-523.

Worline M. and Dutton J.E. (2017) Awakening Compassion at Work: The Quiet Power that Elevates People and Organizations. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Xu, A.J., Loi, R., and Ngo, Hy. (2016) Ethical Leadership Behavior and Employee Justice Perceptions: The Mediating Role of Trust in Organization. J Bus Ethics 134, 493–504.

Acknowledgments and thank yous

We would like to thank all of the charity leaders and colleagues who helped to input into the 'Building the road as we walk' research. In particular Caroline Copeman, Christine Fogg, Alex Skailes, and all the CCE consultants for sharing their experience and for their invaluable support.

We would also like to thank the Bayes Knowledge Exchange and Impact Fund (KEIF) for supporting this work.

The future of the research

Like the charity leaders we spoke to in carrying out this research, as practitioner researchers we were also building the road as we walked, and we identified some areas we feel it may be helpful to continue building on further in the future:

- Looking in greater depth and detail at the practices of charity leaders in leading organisations and stakeholders in uncertainty. This could focus on eliciting the views and experiences of particular groups, including customers and people who benefit from the charity’s activities, as well as board members and employees.

- Testing out the themes we identified with stakeholders. This would offer us a more granular understanding of what positive charity leadership during uncertainty entails, drawing on a broader range of experiences and perspectives.

- Looking in more depth at strategies that instil hope.

About terminology

At some points throughout this resource we have used the term 'beneficiary'. We understand that this phrase carries paternalistic connotations and we use it to refer to clients, customers, members, people who benefit from the charity’s activities.

Disclaimer

While great care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information contained in this resource, information contained is provided on an ‘as is’ basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness, timeliness or of the results obtained from the use of the information and The Centre for Charity Effectiveness accepts no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may occur. The Centre for Charity Effectiveness and authors make no representation, express or implied with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this content. The views expressed in this resource may not necessarily be those of The Centre for Charity Effectiveness. Any action you take upon this information is strictly at your own risk. Specific advice should be sought from professional advisers for specific situations.

Contact us and Find Bayes

Contact Details

Centre for Charity Effectiveness

CCE@city.ac.uk